Luiz moved from Sao Paulo to Tokyo when he took the opportunity to study Japanese. As a third generation Japanese-Brazilian, he thought he was familiar with Japanese culture though also said he found himself continuously surprised after he moved to Japan.

Profile

Name: Luiz Nakano Age: 51

Luiz was born in Sao Paulo, Brazil. In 1990, he came to Japan to study language for one year. Then he worked for the former Banco América do Sul, at the Tokyo office. Meanwhile he also worked as a court interpreter for Japanese, Portuguese and Spanish, then became independent as a legal interpreter in 1995.

Is there such delicious soy sauce?

———-Did you have any expectations when you first came to Japan?

Luiz: Yeah. I came to Japan in 1990 for one-year language study program and had various expectations and worries, though there were also things that I never expected that were good.

First of all, the food. I was surprised to know that there existed such delicious soy sauce in Japan. In Brazil, to me soy sauce was just something black and salty. Just an alternative of salt.

When my grandparents moved from Japan to Brazil, seasonings such as soy sauce, miso and bonito flakes were not available there at all. So Japanese families would make them on their own at home; I would help them make them. We would make them very salty so they could be preserved for a long time.

I was surprised when I came to Japan. Soy sauce was not just salty, but also had tastes and flavors. Bonito flakes were so thin and beautiful. I had only seen the one in powder form back in Brazil.

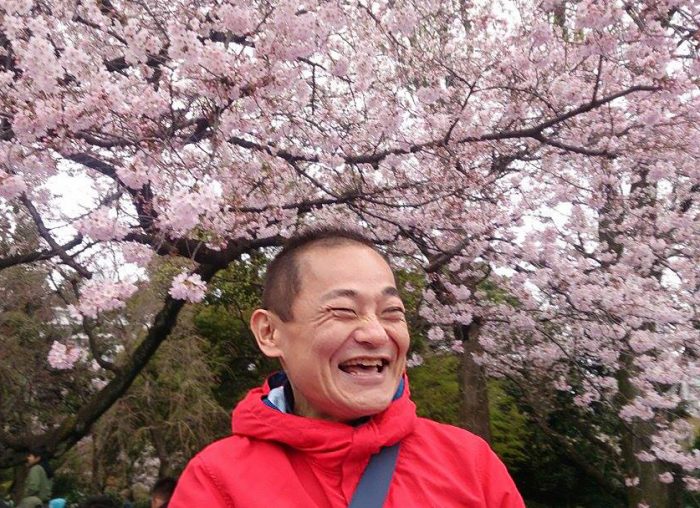

Family picture when Luiz was little (the second from the left)

Family picture when Luiz was little (the second from the left)

Luiz: Another thing that was unexpected was the way Japanese people communicated. In Japan, if you visit someone’s house, they would be very kind to you like, “This is what the hospitality is”. In Brazil, people would never welcome you in Japanese houses in a warm manner.

The Japanese who moved to Brazil were extremely wary. In short, during the wartime, Brazil was on America’s side, which makes Japanese people an enemy to them.

So when Japanese people gathered together and talked in Japanese, a language Brazilians don’t understand, that itself would make them targets to arrest.

So even among Japanese people it was hard to be welcomed unless you know them for a long time. Even in that case, still you had to bring a fancy gift without exception.

When I came to Japan, hospitality here was surprising to me. It felt almost like a celebration all the time.

Japanese language that does not translate

———- When you first came to Japan, what was your Japanese like?

Luiz: At first, I was filled with confidence. When I was little my grandparents often would look after me and would teach me Japanese. My Japanese got across to Japanese travelers in Brazil; that made me think that I was very good at it.

After I came to Japan, however, when I spoke it, it didn’t work. People laughed at me when I talked. I wondered why and did some research to find out that the words and phrases my grandparents taught me were old-fashioned. For example, Choumen(帳面). It means a notebook.

I was in shock when I found out. People said to me “We don’t use those old words much anymore.” I lost my confidence to speak Japanese. There was a period of time that I did not want to meet anyone.

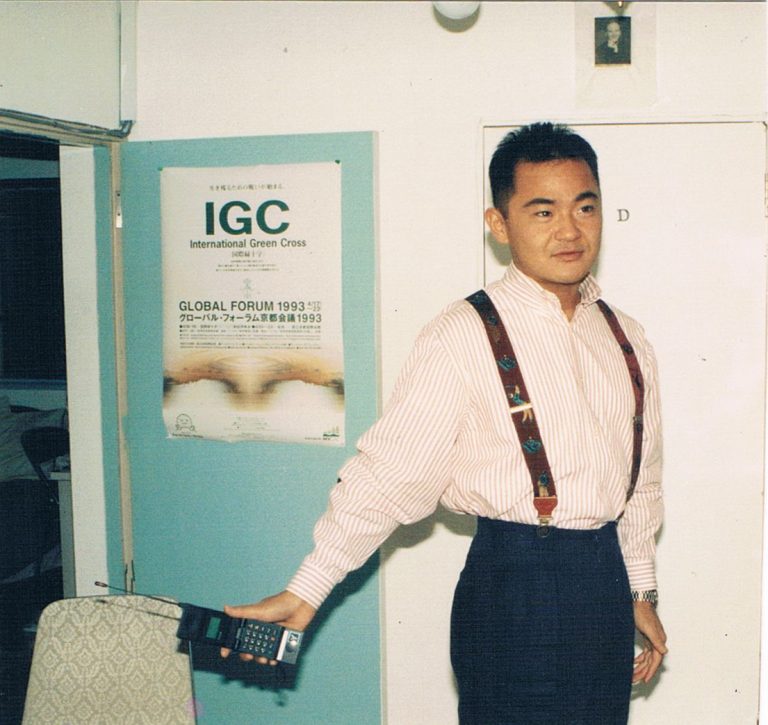

At the airport when Luiz (the third from the left) first came to Japan

At the airport when Luiz (the third from the left) first came to Japan

“Go see a wider world”

———-What did you do after your period of study in Japan was over?

Luiz: By the time I was going back to Brazil, I had a three-year job offer from Banco América do Sul of the time. As the job was not relevant to what I had been studying, I was very hesitant to take it.

The person who gave me a push to come to Japan was my grandpa. Saying, “go to Japan and see a wider world”, he was very supportive. Then grandpa told me, “If you have such an offer, then of course don’t you come back here”. Then I did as he told me to.

———- What did you yourself feel about it?

Luiz: I wanted to go back to Brazil! I had friends there. Plus winter in Japan is cold. Though grandpa was an overwhelming figure to me; if he said something, even my strong father could not stand before him. For our family, he was something like God.

Job at the bank, becoming a legal interpreter

———-What kind of job did you do at the bank?

Luiz: I was assigned to a department of money transfer for foreign currency saving. My job was to open an account for Brazilians who came to Japan for work, and send their money safely to their family back home.

That was when the bubble collapsed and there were 250,000 Brazilians in Japan. They were working really hard, at factories and also for the types of jobs that Japanese did not want to do, exhausting labor such as asbestos elimination, night-shift work checking railways, cleaning large vessels and welding.

———- How did you start working as a legal interpreter?

Luiz: At the bank, there was a customer who was a judge at Tokyo District Court. The judge once was in a rush looking for an interpreter for a trial of a Brazilian; the time and date of the trial matched with my schedule, so I went there to do the job.

After the trial, they said I did the job well and also kindly asked me if I would be able to do the job again. Then I enrolled in the seminar to become an interpreter officially.

———- So you started to work as a court interpreter like a side job?

Luiz: That’s right. In general it is hard to imagine having a side job while working at a bank, which is such a rigid place.

Though the manager of the branch at the bank was like: “I am so proud that someone from our bank is helping at the courthouse!“ [laughs]. The exam to become an interpreter was hard, but I was able to pass.

———- When you became independent as an interpreter, did you prepare something?

Luiz: Before my contract ended, Banco América do Sul went bankrupt and it became quite a big scandal. An Italian bank acquired the bank; Banco América do Sul became Sudameris Bank.

Around the time, in advance of the acquisition, they started to have more work for me at a courthouse. When the economy is so bad that a bank goes bankrupt, there seem to be more crimes.

———- I see. Then you had enough work when you left the bank.

Luiz: Yeah. Though I was very anxious if I would make it through as a freelancer. Till the time I had all the security of my work at the bank and all that was disappearing.

So before I became independent, I visited the customhouse and immigration office assuming they must need interpreters before and after a trial. The timing was amazing. Apparently it was just the moment that they really needed interpreters, so it was like, “We were waiting for you!”

However, they wouldn’t like to have just anyone. They want to know your background. They asked questions to confirm who I was and my abilities. I showed them that I worked at courthouse, which led them to hire me.

Just like that, I visited one after another from custom office, immigration office and the Bar Association. Just as before, as I showed them that I work at court, they accepted my offer.

———- How long have you been working as a legal interpreter?

Luiz: It has been already 25 years now.

Grand parents’ relocation to Brazil

———- Where did you grow up?

Luiz: Sao Paulo city, Sao Paulo state. We used to live with my grandparents of my mother’s side. My parents were not home during the daytime for work, so my grandparents basically raised me.

———- Can you tell me about when your grandparents moved from Japan to Brazil?

Luiz: Sure. My grandparents of my father’s side, they were a coffee-farming family in a town called Pereira Barreto. It is located northwest from Sao Paulo state.

Listening to their stories, how much hardship they went through moving to Brazil, it motivates me that I have to try harder.

Today, even if it takes 30 hours by flight, you can always come back. However, it took 30 days by ship back then. Furthermore, if someone caught malaria on the way, the person had to be executed right there so that other people did not get contaminated. Then they removed the body from the ship, because it would be hopeless if the ship spread the infection.

These days when going to Brazil, people complain about things such as, “ There is no electric toilet seat”. In past, what people would complain about were things like if they received properties or not. Those things could not be changed right away; they had to get by with what was given to them.

———- When was their relocation?

Luiz: After the World War Two. My grandparents on my father’s side took a ship called Santiago-Maru. It sailed from Kobe harbor. When it departed, they waved their hands and said, “We will work hard and send you money”, “We will be back,” and people saw them off.

When they arrived in Brazil, things were not as they were told at all. They were given the land which Brazilians found impossible to do anything. Their debt increased rather than their savings. “We may not be able to go back to Japan ever again.” — that was what they thought.

The Japanese people who relocated to Brazil before the war already had their own land. They made an association and welcomed newcomers. As time went by, some people sent money to their family and friends in Japan.

Even just a greeting style is different

with Luiz’s relatives in Japan

———- What do you miss the most about Brazil?

Luiz: It depends on the time. If you compare Brazil and Japan, even just a greeting style is different from hugging to bowing. It is different how work is supposed to be, how the medical system works; how they support those who commit crimes to rehabilitate is also different.

There are just so many aspects that feel, “It is this much different from Brazil,” which makes things even more fun.

———-What made you happy after you came to Japan?

Luiz: There are too many. There are just so many cute guys [laughs].

Living in the gay world, it is tough. Everyone wants someone who is great looking, intelligent, attractive and with a good income. It’s almost a fantasy. Plus even if you were not like that, they would try to pretend like, “I am that kind of guy”.

It is not just in Japan though, anywhere in the world. It is the same in Brazil.

And the bigger age gap there is between two, the more it typically becomes related to financial things. When you get used to the way things are, you just start to take it as something normal and go out with those who enjoy having the financial advantage.

That is why though, it surprises me when I meet someone young who does not have that kind of value.For example, I have a cute gay friend who is about 20 years old. When we planned to have dinner for the first time, work came up at the last minute; I was about one hour late to meet him. I was amazed that he was still there waiting for me. Furthermore, after we had dinner I offered to pay. Then he suggested we split the bill. Even after making him wait for as long as one hour, can you believe it?

I used to think that some younger men get interested in me because I work out, and that was right.

Though what they want is not exactly what is simply physical. There are more of those who ask me: “What should I do to make my abs like yours?” or “Let’s go cycling somewhere”. That sort of interaction makes me happier.

———- Is it alright to write about being gay?

Luiz: Yeah, sure. That would make me feel a bit easier. I would be happy if the cute guy that I am interested in these days would read this article!

Now I am 51 years old. Lately when I meet someone from my generation, many are not interested in themselves, like at all. They don’t care about their appearance, they tend to be just all talk and only brag about the things they did 20 or 30 years ago. I used to hate that when I was younger, so I would never do that myself.

———- Would you consider relocating again?

Luiz: Yes. I would go to Spain. Before I came to Japan, I studied there for about half a year.

I have been working hard in Japan up until now, though I feel like I have not seen much of the world. While I am healthy and well, I feel I need to move around and see more. I can do my job as an interpreter in Spain too.

———- Would there be anything you would like to add?

Luiz: There are many who cannot do well after relocatng, right? In my opinion, when in Rome, do as the Romans do. If you are not prepared to do this, you should not move abroad. It is not good to force everything that you are used to, to the people where you relocate to.

So those who think like “I don’t want to learn anything about this country”, they should not go there. You have to have respect the people in the country where you move.Mea